Winning Elections is a Science

It's time for a new era of political strategy

"Half the votes plus one." Everybody knows what it takes to win an election. But potential strategies to get there are infinite, and campaigns spend significant sums on strategic consultation. Yet, another maxim in the world of political strategy is that it's okay to win using innovative tactics, but it's not okay to lose using them. As such, despite consistent publication of new research, strategies implemented tend to be stagnant.

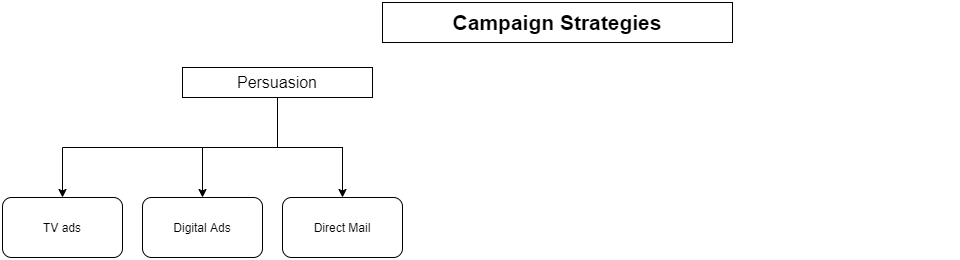

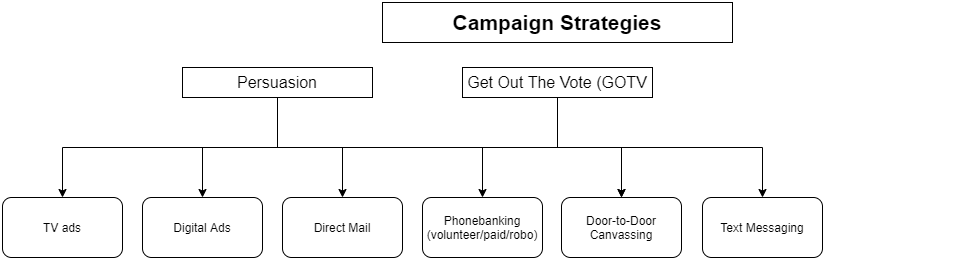

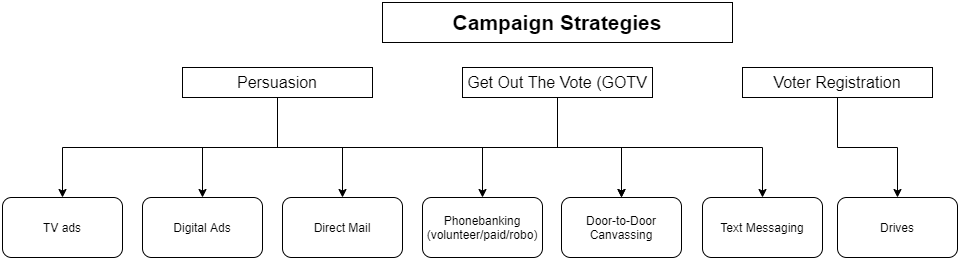

Much of the outreach we're all familiar with appears to be trying to convince voters of some candidates virtues (or vices).

Supporters are also "touched" as many times as possible to encourage them to actually get to the polls.

And campaigns with enough resources sometimes even try to help citizens exercise their civil rights.

But research has put the whole persuasion paradigm into question

For example, researchers at UC Berkeley and Stanford conducted a meta-analysis of 40 field experiments and 9 original field experiments to measure the true effect of campaign contact and advertising. This graph shows the average of their data for general elections. Short of sending the candidate to every door in the neighborhood, campaign tactics to change minds are just adding to the noise.

It's more feasible to get your existing supports to vote - but at what cost?

Get the base to the polls. Sounds simple, but a lot of factors impede would-be voters from turning in their ballots (source). Many options exist to help them along, but most of them aren't cheap. Fortunately, seasoned political science researchers Donald Green and Alan Gerber have been synthesizing research on the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of different voter mobilization strategies since 2004 in their book Get Out The Vote. Their most recent version, which incorporates the most recent cutting-edge research on voter mobiliziation, was published just last year. For the tactics that showed a statistically significant positive effect on turnout, they calculate an estimate of how much they end up costing per additional vote garnered...

As it turns out, votes aren't cheap. But if campaigns diverted some of the millions of dollars they spend on advertising to GOTV, they might actually move the needle.

But is persuasion really impossible?

Or are the standard approaches just bad?

In the last few years, a strategy known as "Deep Canvassing" has gradually been subjected to the tests of scientific research. Earlier this year, a new paper conducted three experiments to separate and measure the effect of what is academically known as "non-judgmental exchange of narratives," whether they be in-person or by phone. The researchers looked at a couple of different issues / policy subjects, and found statistically significant effects that endured at least 3 months post-conversation. From the study:

"Examining results on dichotomized versions of the individual items in the policy index, the average share of inclusive policies individuals strongly supported increased from 29% in the Placebo condition to 33% in the Full Intervention condition (p <0.01). For example, while the Abbreviated Intervention had no effect on individuals strongly supporting granting legal status to people who were brought to the US illegally as children and who have graduated from a U.S. high school, individuals assigned to the Full Intervention were 4.7 percentage points more likely to indicate strong support (p <0.04). Likewise, when dichotomizing the policy items by whether individuals supported each policy at all, instead of expressing indifference or opposition, the share of policies individuals supported at all increased by 2.2 percentage points in the Full Intervention condition (p= 0.058). Note again that all these estimates are intent-to-treat estimates and that the compliance-adjusted estimates would be larger."

So perhaps the traditional methods of persuasion are the real problem, not the idea of persuasion itself. Still, more research is needed to validate those findings. As such...