THE PLANET NEEDS YOU

TO TAKE PICTURES OF BUGS

Anthropogenic climate change has threatened much of life on Earth.

There has been increased focus on how our actions and a warming planet have exacerbated biodiversity loss, to the point that conservationists have labeled the Anthropocene as the sixth great extinction event this planet has faced.

However, much of this attention has failed to look at the roots.

Animal biodiversity loss is a wide-spread issue, yet Earth's smallest species have been widely ignored. We need to start asking "what about bugs?"

WE LIVE IN A WORLD OF BUGS

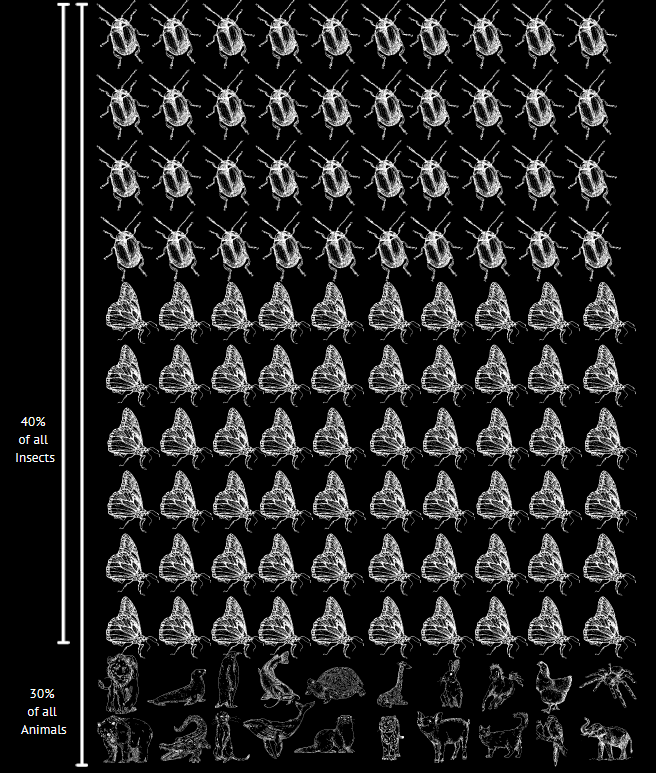

If someone was asked to describe Earth's animals, they'd overwhelmingly be talking about insects.

Biodiversity encompasses both the number of species and the total population of each species. No matter how you slice it, insects have every other taxa beat.

From the majestic butterflies of Lepidoptera, the eusocial bees and ants of Hymenoptera, to the rainbow array of beetles and weevils in Coleoptera, the 29 orders of insects represent a wide array of diversity.

If every one of Earth's animal species were given equal representation, over 80% of them would be insects.

Coleoptera alone is more than:

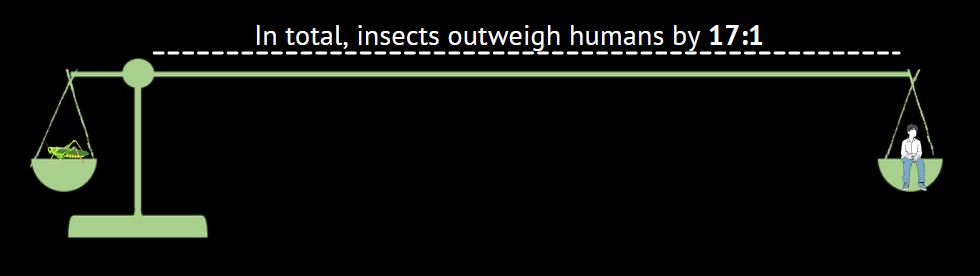

Even with their small stature, insects make up the majority of the world's animal biomass. For every 1 human, there is an estimated 1.4 billion bugs. Pound for pound, insects outweigh humans 17 times over.

While they may not be as alluring as the tiger, or as endearing as the panda, insects are a major component of Earth's life. Any conversation about biodiversity that omits this group is missing the big picture.

Photo by Egor Kamelev from Pexels

Photo by Egor Kamelev from Pexels

Photo by Brandon Phan from Pexels

Photo by Brandon Phan from Pexels

Photo by Skyler Ewing from Pexels

Photo by Skyler Ewing from Pexels

Photo by Egor Kamelev from Pexels

Photo by Egor Kamelev from Pexels

AN UNTOLD STORY WITH A FRIGHTENING ENDING

Despite being the majority of species, insects aren't getting the same attention as other animals.

Despite their prevalence, insects are under-represented in conservation efforts. We're still not able to fully understand how anthropogenic climate change has threatened these species, primarily because we're not looking.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is a leading authority in understanding threats to biodiversity. They have committed to documenting and assessing every species, but progress has been slow for invertebrates.

The IUCN Red List, compiled by conservationists and field operators worldwide, represent where our focus has been in conservation. It's one of the best summaries of who is being studied, and who is being ignored.

Without this data, conservationists are restricted in their ability to understand the impact our activity has had on these species. They also cannot bring awareness to the issue.

Just because we're not addressing the crisis doesn't mean it's not there.

Could it be that we're not focused on insects because, on the whole, they're not in danger? After all, there are a lot of bugs, with more species being discovered daily. Maybe insects are actually thriving?

Unfortunately, no. While we have little information, what we do know paints a grim picture.

Despite being the least evaluated taxa, the proportion of insects that are threatened is on-par with their vertebrate cousins.

We have no way of estimating the real threatened rate without more data, but considering most of the evaluated species are from the most prevalent populations, more data is likely to present a worse picture, not better. If we're optimistic, 19% of insects are threatened with extinction. In reality, it could be much more.

There have been efforts to understand the true rate of insect biodiversity loss. Stanford's Francisco Sanchéz-Bayo has made it a personal mission to bring insect loss into public attention. His work with Kris A.G. Wyckhuys on the Worldwide Decline of Entomofauna compiled field research from 73 historical studies to provide a methodology for estimating insect loss.

Their results are worrying. It's estimated that insect biomass - the total population of all species - has been declining by 2.5% annually.

Let's think about what that means. The graphic below outlines that loss at that rate means that 25% of insects will be gone after 10 years. After 20 years, we'll have half as many bugs as before, and at 40 we'll have none at all.

The Big Question: When was Year 0?

If it's 2022, we have 40 years before all bugs are extinct. If it's earlier, which Sanchéz-Bayo believes it is, we could have much less.

A WORLD WITHOUT BUGS

We've barely scratched the surface on how much insects influence our life.

Because we still have so little data, the full extent of ecosystems' reliance on insects is still unknown. We have barely begun to study how insect loss is affecting other species, though preliminary studies indicate that insectivores are suffering more than omnivores.

Whether we know enough to conclusively identify the causes and effects of insect loss is contentious. IUCN provides a list of threats for every assessed species, but applied ecologist Robert R. Dunn and others make strong arguments that traditional conceptions may be incorrect, and more data is needed.

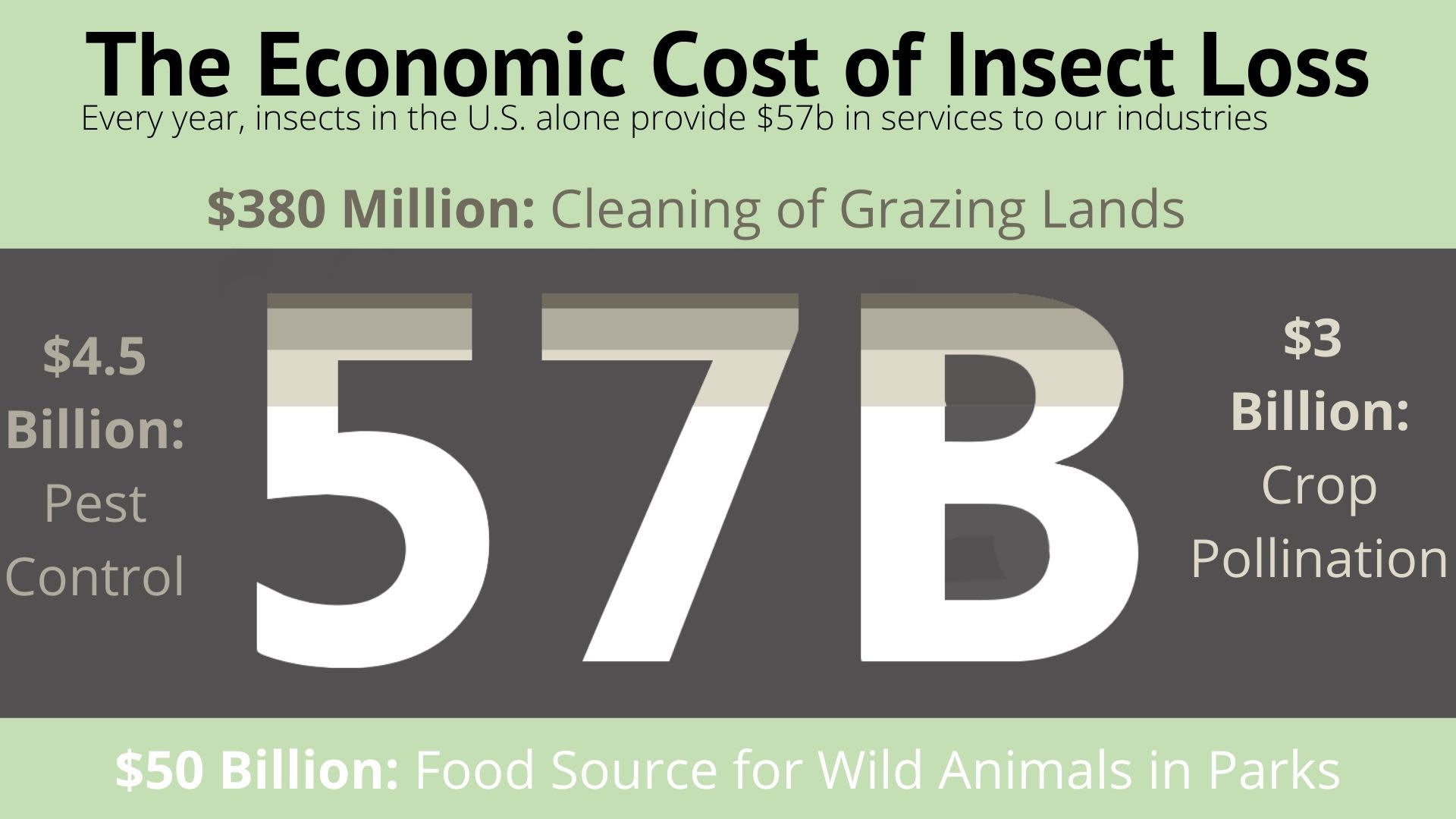

Entomologists are still working to understand what a world without insects - pollinators, decomposers, and pests alike - would really look like. Cornell's John Losey has taken a unique approach with economics, estimating that in the U.S. alone the contribution of insects is valued at over $57 billion a year.

WHAT WE DON'T KNOW MATTERS

The biggest barrier to Intervention is Information.

We need to understand how insect populations are distributed so entomologists can look for fragmentation - a key indicator that a species is threatened.

Without more data, we can't:

- Confirm the Causes

- Identify the Scope of Effects

- Make Policy

The reason we know so little? Awareness, but also manpower.

Entomologists and conservationists are working hard to catalogue and understand insect biodiversity loss. But with the clock ticking down, we're running out of time.

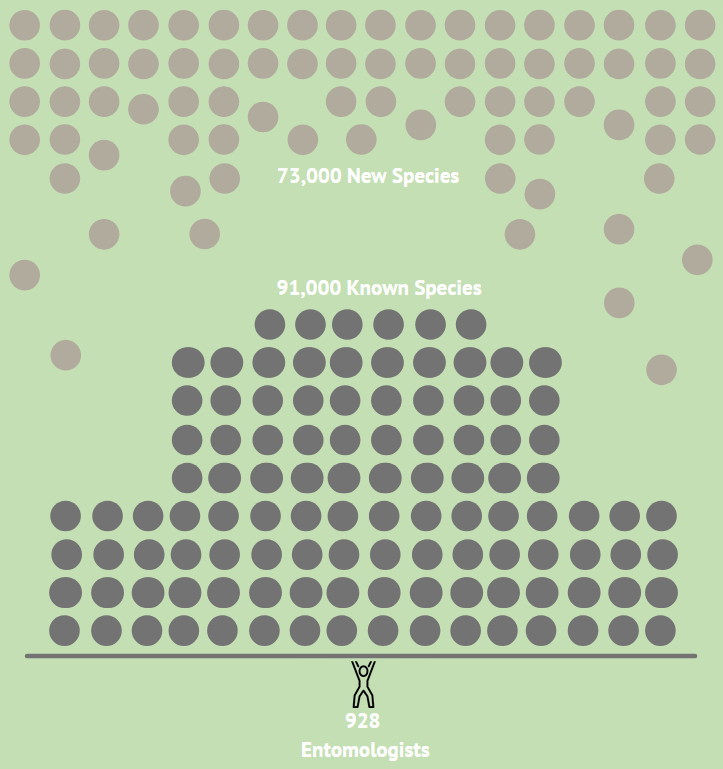

This is because we simply don't have the manpower. The same reasons insects are important - species diversity and biomass - are the reason it's such a daunting challenge.

In the United States alone, 91,000 insect species have been identified, with an estimated 73,000 species left to find. Even if conservation professionals focused on known species, the 928 entomologists we have would need to take on nearly 100 each.

Mapping population distribution, a key indicator for threat of extinction, means the geographical scope of the fieldwork required is staggering.

There are (at least) 98 species for

every 1 entomologist

WANT TO HELP? MEET YOUR NEWEST MODELS

What if we could reduce the fieldwork load? Citizen science, the voluntary participation of the public to crowdsource data for researchers, can leverage all of us to bring insights no scientist could find alone.

Entomologists need population data; what insects are there, and where are they found? By compiling individual observations, we can help build the bigger picture.

iNaturalist, and apps like it, are made for this mission. Millions of observers take pictures of the animals they see, which are then identified by hundreds of thousands of citizen scientists. The data is automatically compiled and mapped, ready for entomologists to use.

Simply shoot, upload, and know you're making a difference.

Attributions

All datasets used in this publication are available here, with original authors cited.

Additional photos courtesy of prasanthdas ds, Kasuma, DSD, Pixabay, Egor Kamelev, W W, & Jan Venter