The History of Lines in a City

In Pittsburgh, the consequences of redlining are still clear 90 years after the first lines were drawn.

In the 1930s, the U.S. began a massive campaign to promote homeownership. From 1933 to 1934, Congress created the Home Owners' Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration, two federal programs which insured private mortgages for the first time.

The intervention dramatically reduced interest rates and required down payments. In the 30 years afterward, homeownership doubled.1

This unprecedented rise in homeownership was reserved for white Americans only. The Home Owners' Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration pioneered the practice of redlining, granting loans only in white neighborhoods and only to properties with white-only restrictive covenants.

Across the country, the policy was the same: no mortgage guarantees for Black people regardless of creditworthiness. The FHA also refused to finance new housing developments, like Levittown, PA, unless they were whites-only.2

Segregationists were in power at every level, from the Real Estate Boards and the zoning offices to the banks that made the loans. At each step, these segregationists had the means to prevent Black people from owning homes.

The federal government's segregationist effort was led by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation, which commissioned local property assessors to make maps to inform lending federal lending practices.

In 1935, these federally-backed assessors came to Pittsburgh.

Working under the Home Owners' Loan Corporation, they created so-called "Residential Security Maps." Assessors gave neighborhoods a score – "A" through "D."

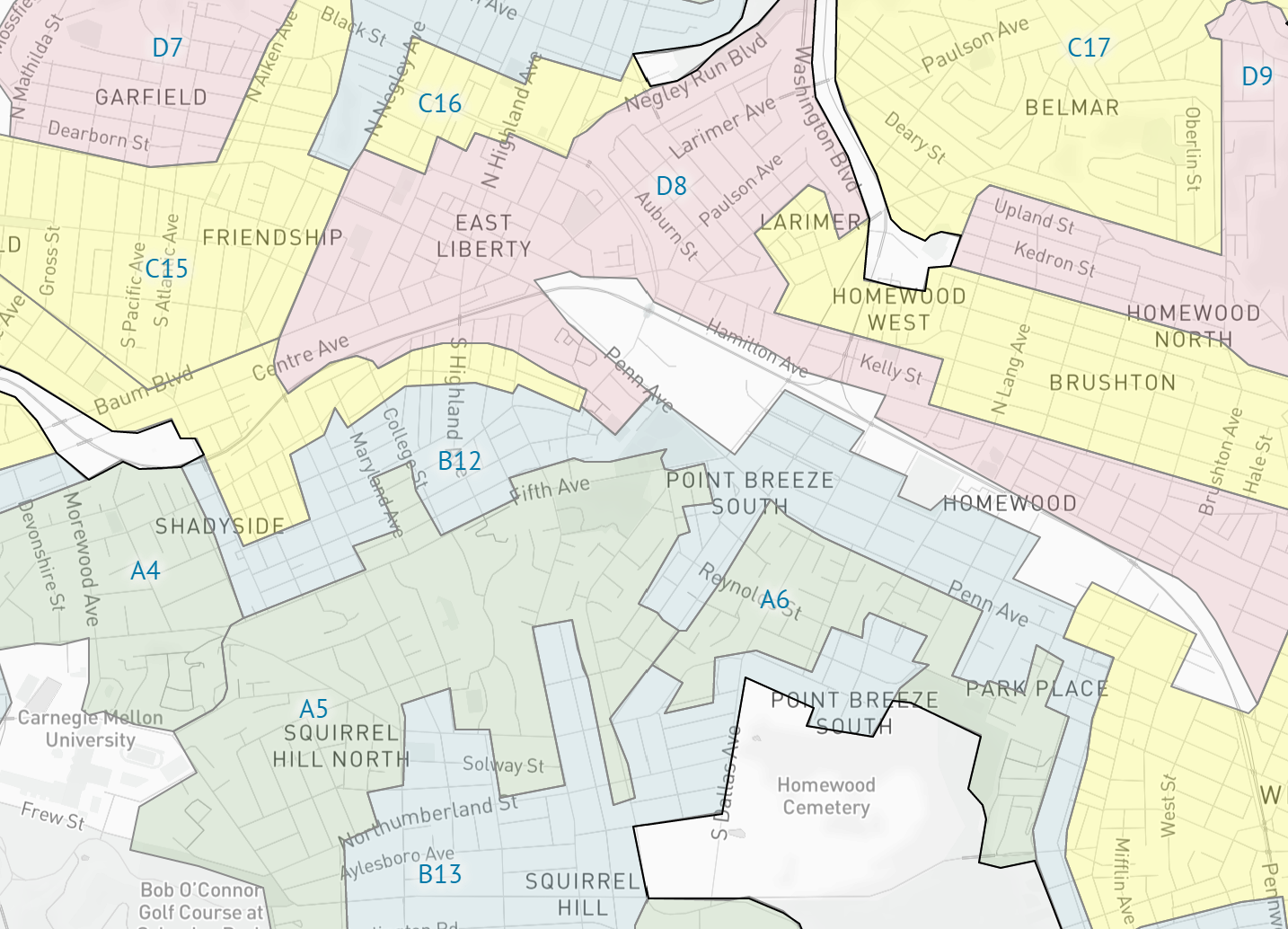

The HOLC map of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania showing neighborhoods divided into four grades.

The HOLC map of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania showing neighborhoods divided into four grades.

“A” neighborhoods were identified as “in demand” and were colored green. “D” neighborhoods were considered “declining” and were shaded red. Neighborhoods with Black residents were almost always given “D” ratings. "D" ratings meant residents would receive no mortgage support from the HOLC nor the FHA.

The goal was to make homeownership in "D" neighborhoods practically impossible. By in large, this effort was successful. "D" neighborhoods recieved fewer loans and had far lower rates of ownership.

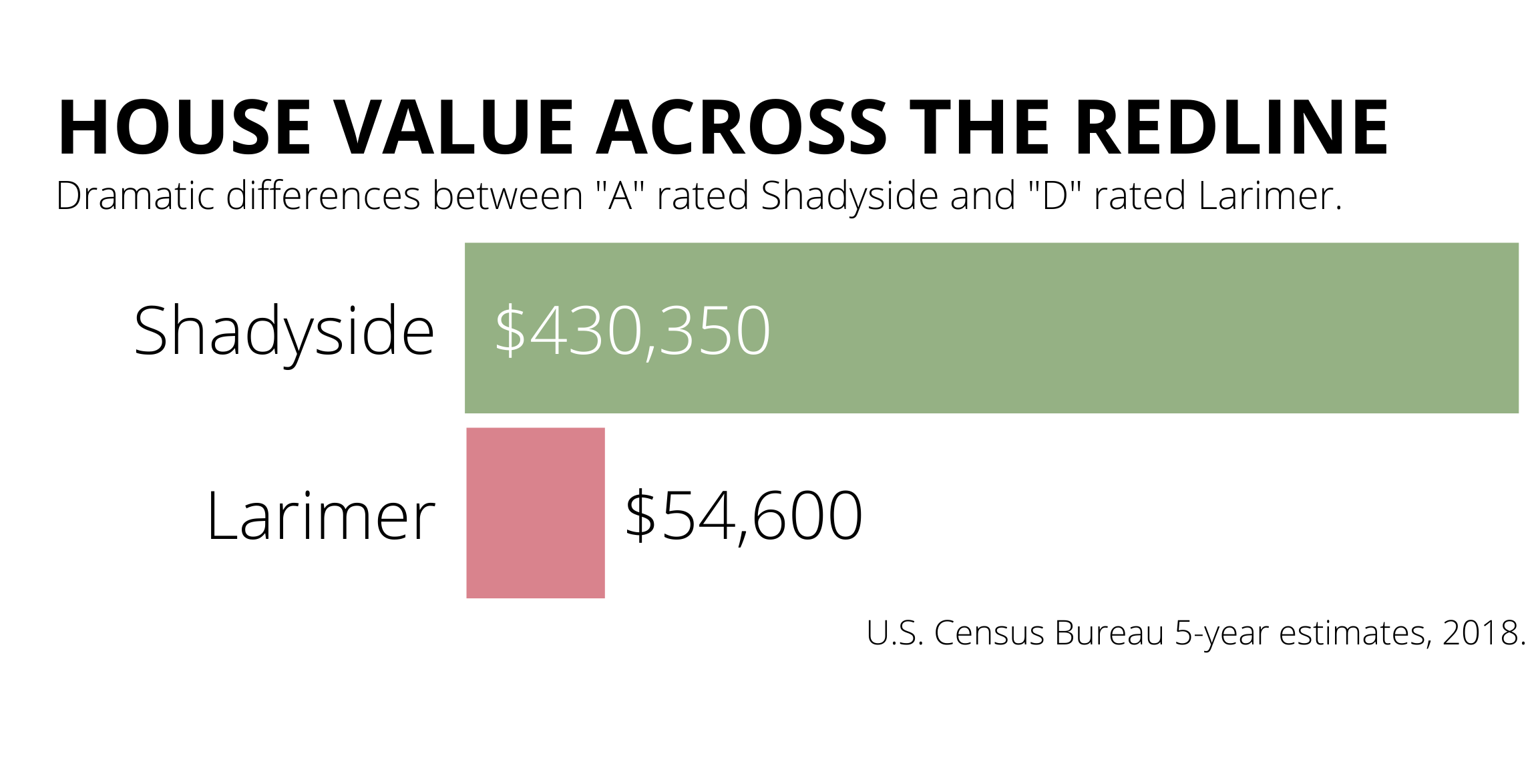

In Pittsburgh, adjacent neighborhoods might receive drastically different grades.

HOLC Residential Security Maps highlight how different even adjacent neighborhoods were graded.

HOLC Residential Security Maps highlight how different even adjacent neighborhoods were graded.

White neighborhoods – like Squirrel Hill or Shadyside – were described as “white-collar class," with "professional executive men." They received “A” and “B” ratings, shaded in green and blue.

Neighborhoods across the road – like Larimer and East Liberty – recieved drastically different "assessments." These neighborhoods were described as "contaminated" having a high "concentration of foreign-born" and Blacks. They were given “C” and “D” ratings.

Today, those same neighborhoods have drastically different housing markets.

By reducing the amount of capital available, redlining artificially lowered neighborhood house value. Owners in non-redlined neighborhoods had more money to invest in their properties, which then sold at higher values. This lead to more wealth for the individuals and the community.

Redlined neighborhoods, on the other hand, had less access to capital and lower reinvestment rates, leading to lower values.

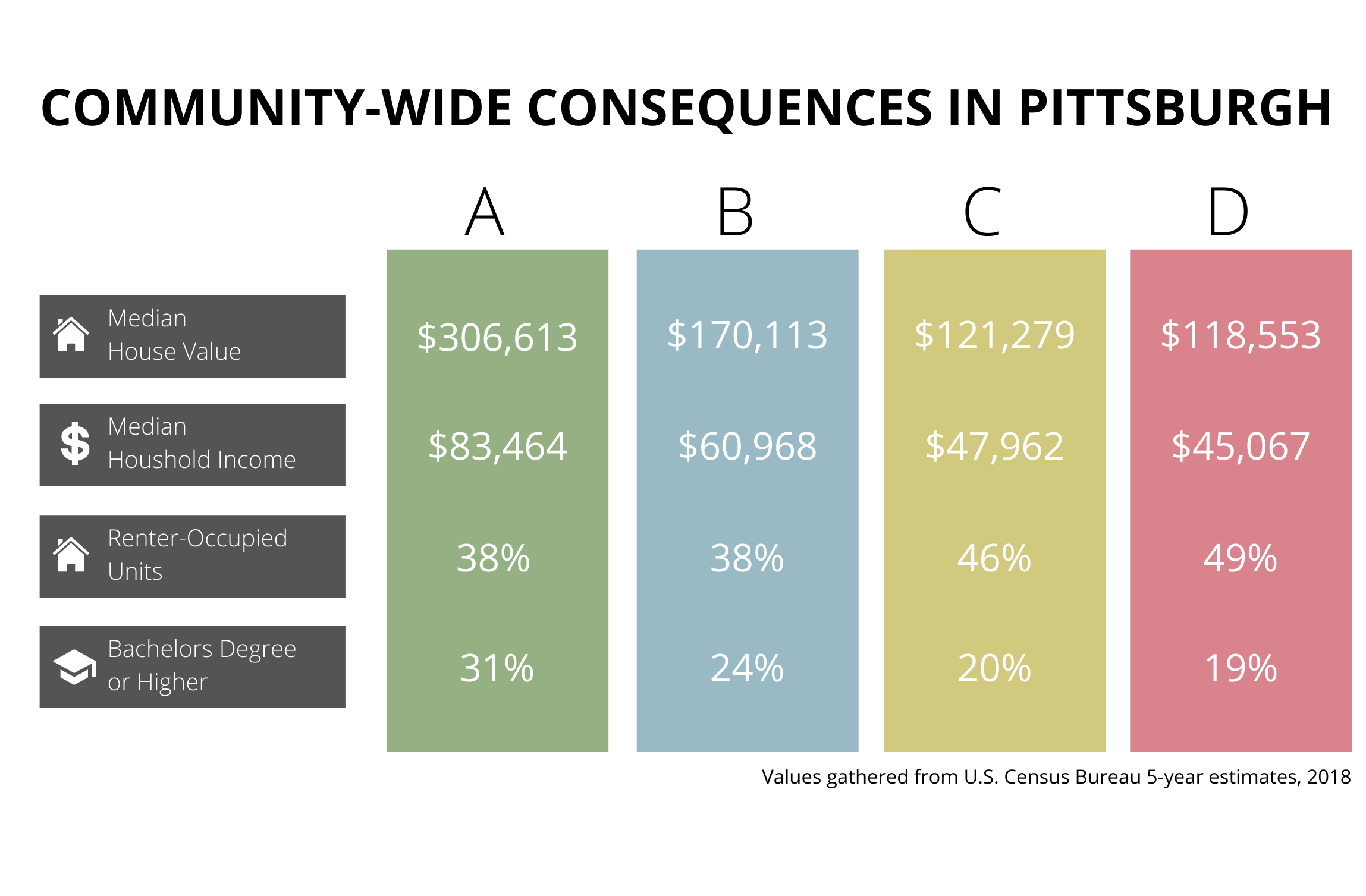

Nearly a century after the maps were made, the cumulative effect can still be observed. The distribution of sale price across grades follows the same pattern: houses in lower graded neighborhoods sell for less.

Bigger than Housing Policy

Redlining "D" neighborhoods had effects on nearly every measure of community well-being. These differences are a direct result of the disinvestment in Black communities.

These aggregate statistics do not represent the full extent of inequality between white and Black Pittsburgh residents. Consider that some "D" neighborhoods have become recent targets of gentrification, where developers capitalize on the undervalued housing caused by redlining.

Regardless, there are large disparities between Black and white Pittsburghers. A 2019 study on Pittsburgh inequalities across gender and race found that Black residents have worse health, income, employment, and educational outcomes than white residents. The study found in Pittsburgh Black people faced worse outcomes than Black people in other cities.3

Toward Solutions

Redlining was just one of the tools the U.S. government used to remove wealth from Black communities. There were also 250 years of Slavery, decades of Jim Crow segregation, the denial of voting rights, the war on drugs, discrimination in schools, and a widespread campaign of mass incarceration.

The combined consequence of these policies is significant. Currently, the average white family has 10 times the amount of wealth as the average Black family. White college graduates make 7 times as much as Black college graduates.4

The scale of the inequities means no single housing or tax policy change will remedy the massive scale of the U.S. government's removal of Black wealth. Instead, the United States must restore that deferred wealth through reparations paid in the form of cash payments and wealth-building opportunities that address racial disparities in education and housing.

"Though remote in time from the period of enslavement," writes U.S. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee, "these racial disparities in access to education, health care, housing, insurance, employment, and other social goods are directly attributable to the damaging legacy of slavery and racial discrimination."5

Representative Jackson Lee has filed bill H.R. 40 in congress, which would create a commission to develop proposals for providing reparations to African Americans. Jackson Lee describes H.R. 40 and the movement for reparations as less focused on direct cash payments and more a focus on potential remedies for the sustained damage of slavery and systemic racism. In this way, H.R. 40 hopes to explore the unaddressed moral issues "that continue to haunt this nation."6

Take Action and Learn More

The movement for reparations is built upon the work of generations of Black activists and scholars. In 2014, journalist and author Ta-Neishi Coates reintroduced the issue into the national conversation in a 2014 article titled "The Case for Reparations." Read the article and hear the full case here.

Support bill H.R. 40. You can find a list of co-sponsors and read about the status of the bill here.

Racism like redlining helped some communities at the expense of others. You can investigate interactive redlining maps here, published by the Mapping Inequality Project. Consider how your neighborhood, in Pittsburgh or elsewhere, may have benefitted from these government policies.

References

[1] Jackson, Kenneth T.. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, USA, 1987.

[2] Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. United Kingdom, Liveright, 2017.

[3] Howell, Junia, Sara Goodkind, Leah Jacobs, Dominique Branson and Elizabeth Miller. 2019. "Pittsburgh's Inequality Across Gender and Race." Gender Analysis White Papers. City of Pittsburgh's Gender Equity Commission.

[4] Ray, Rashawn and Perry, Andre. "Why we need reparations for Black Americans." The Brookings Institution. (April 2020)

[5] Jackson Lee, Sheila. "H.R. 40 Is Not a Symbolic Act. It’s a Path to Restorative Justice." May 2020.

[6] Ibid.