Smart speakers & privacy choices

Are companies offering clear information & usable controls?

A (very) brief history of voice assistants

Siri debuted on the iPhone in 2010, popularizing the use of voice assistants on smartphones.

Amazon Echo devices featuring Alexa technology were released to the public in the U.S. in 2015. Since then, voice assistants and smart speakers have continued to grow in popularity each year. Amazon has since released other devices that use Alexa voice technology, including the smaller Echo Dot shown to the right.

Siri icon via Wikimedia Commons, user TKsdik8900, CC BY-SA 4.0

Siri icon via Wikimedia Commons, user TKsdik8900, CC BY-SA 4.0

Echo Dot photo via Wikimedia Commons, user Gregory Varnum, CC BY-SA 4.0

Echo Dot photo via Wikimedia Commons, user Gregory Varnum, CC BY-SA 4.0

Google released its smart speaker, the Home, in 2016, and followed it with products such as the Home Mini and the Nest smarthome hub. These products use Google Assistant technology.

Apple released its HomePod, a smart speaker that incorporates Siri technology, in 2017.

Photo of Google devices via Wikimedia Commons, user Y2kcrazyjoker4, CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo of Google devices via Wikimedia Commons, user Y2kcrazyjoker4, CC BY-SA 4.0

Apple HomePod photo via Wikimedia Commons, user SimonWaldherr, CC BY-SA 4.0

Apple HomePod photo via Wikimedia Commons, user SimonWaldherr, CC BY-SA 4.0

What are smart speakers?

In this report, I'll mostly be talking about devices like the Amazon Echo, Apple HomePod, and Google Home, and not about home devices that have screens (e.g., the Google Nest). When these devices have to interact only via audio and can't provide information using a visual interface, there are special considerations for how to help users understand information.

Smart speakers like the Amazon Echo (often just called "Alexa" after the name of its speech technology), Google Home, and Apple HomePod incorporate voice assistants into unobtrusive, always-on devices that can blend into a home environment. This has the potential to be incredibly powerful and has many uses for smarthome ecosystems, handsfree activity, audio listening, information retrieval, accessibility, and other applications.

However, because these devices blend so seamlessly into the home, a space that most people consider private, they also have the potential for privacy invasions.

Image via www.vpnsrus.com, CC BY-SA 2.0

Image via www.vpnsrus.com, CC BY-SA 2.0

Image via Robert Couse-Baker, CC BY-SA 2.0

Image via Robert Couse-Baker, CC BY-SA 2.0

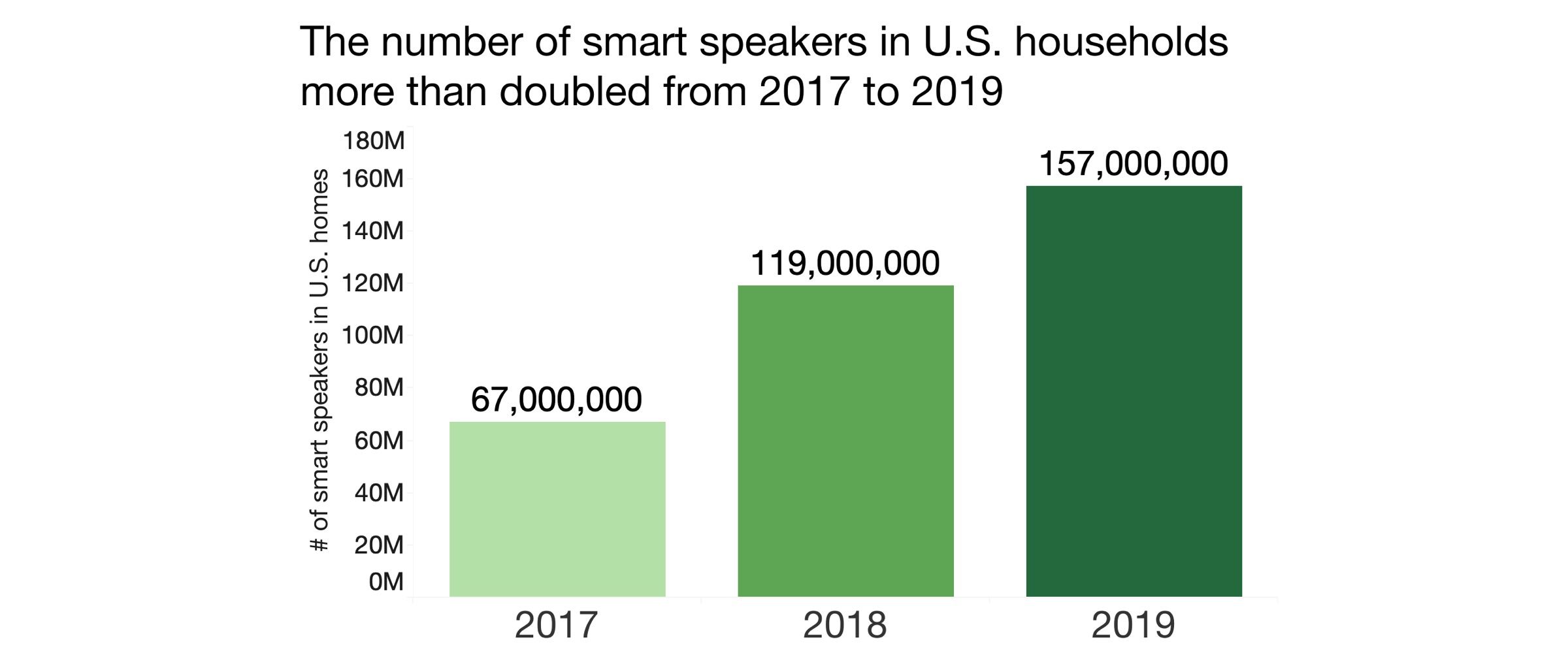

Smart speaker adoption is growing

Smart speakers are becoming increasingly prevalent in U.S households. NPR and Pew reports both show that about a quarter of households had smart speakers in 2019, and the absolute number of devices is growing even faster than that percentage, implying that some households with at least one device are adding additional devices. The number of smart speakers in U.S. households more than doubled from 2017 to 2019.

Data from NPR Smart Audio Report, Winter 2019

Data from NPR Smart Audio Report, Winter 2019

When are these devices listening? And what happens to the recordings?

To be able to automatically detect user input without any physical manipulation, these devices rely on an "always-on" microphone that listens (processing data locally) until a "wake word" (e.g., "Hey Siri," "Ok Google," "Alexa") is detected. When working as designed, the device doesn't save data to your account or send data to the company's servers until that wake word is detected.

Voice recognition technology is not perfect, so this sometimes fails, and recordings may be made and sent to the cloud when the device incorrectly identifies other words or sounds as the wake word.

Until a Bloomberg report in April 2019, it was not widely known that employees or contractors at these companies could listen to recordings to analyze errors and work to improve the quality of the device's responses. These recordings are anonymized in the sense that they don't have names attached, but personnel who have reviewed such recordings report that they often contain sensitive and identifiable information.

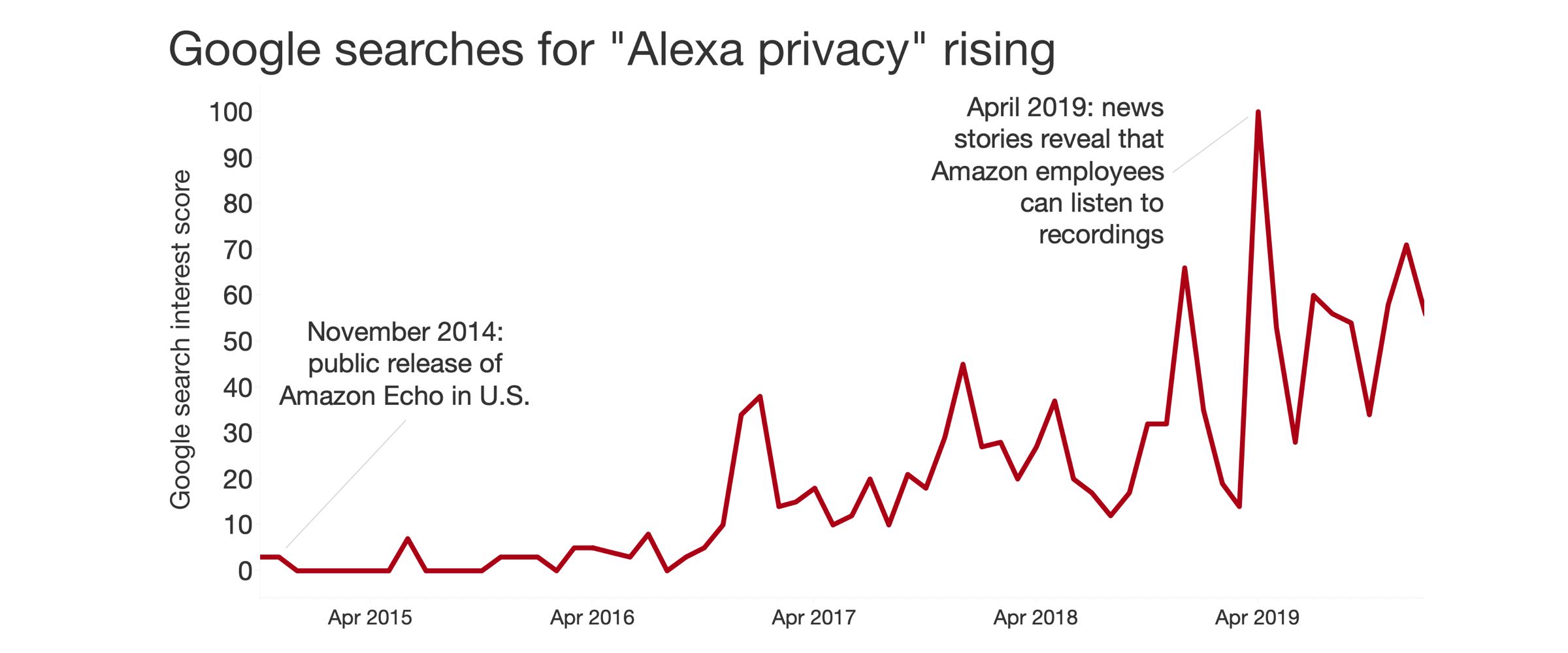

Concern about the privacy implications of these devices had already been growing, but when the Bloomberg article broke in April 2019, interest in those privacy issues peaked. For example, the chart below shows a spike in Google Trends search interest in the terms "Alexa privacy" in April 2019.

Data from Google Trends, January 2017 to December 2019, keywords "Alexa Privacy." Alexa release date from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_Alexa. Note: Google Trends scores are normalized scores based on search interest. 100 is the maximum possible score, indicating high relative interest in a set of search terms. The data used here is drawn from searches in the United States.

Data from Google Trends, January 2017 to December 2019, keywords "Alexa Privacy." Alexa release date from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_Alexa. Note: Google Trends scores are normalized scores based on search interest. 100 is the maximum possible score, indicating high relative interest in a set of search terms. The data used here is drawn from searches in the United States.

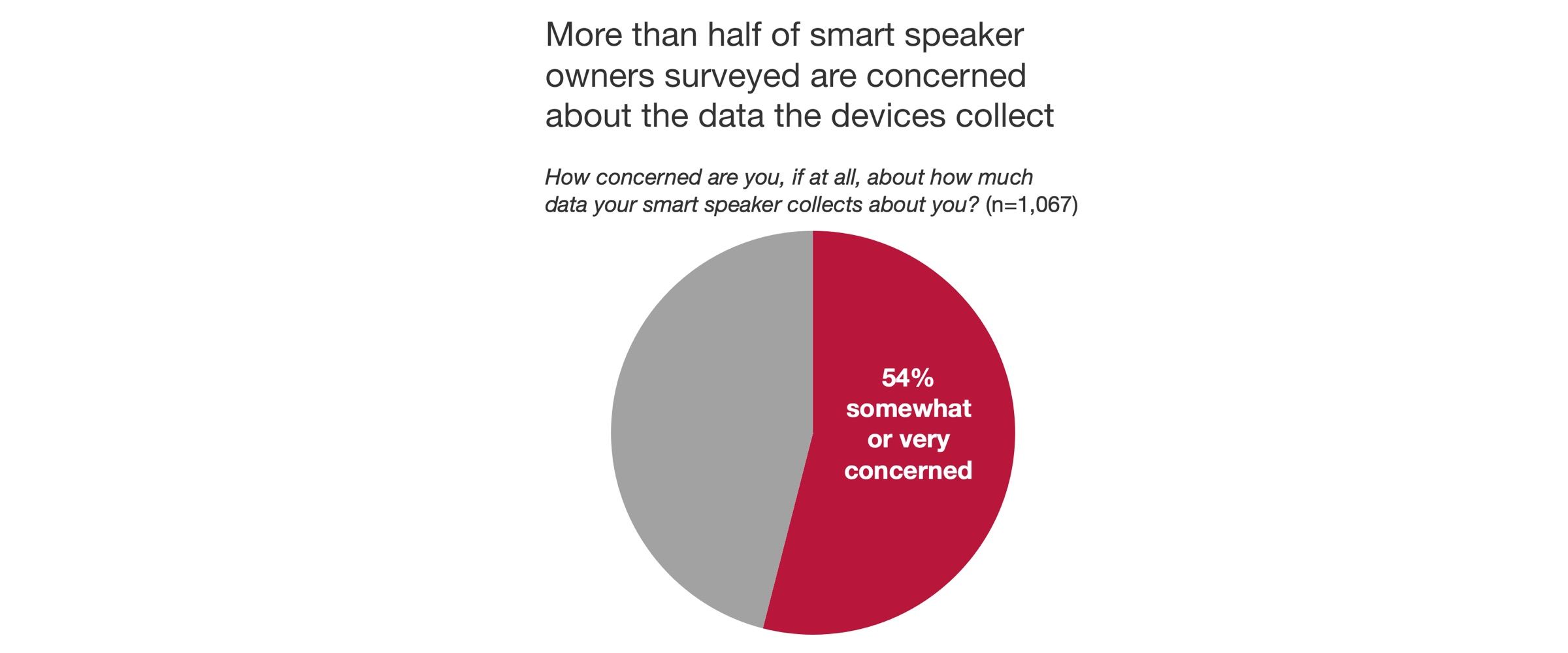

Users are concerned about data collection

Many people just don't see the use for these devices, and some also avoid them specifically because of their privacy implications, according to a Pew report from 2017.

Even among people who do own and use them, though, more than half are somewhat or very concerned about the data that they collect, according to more recent Pew data.

The argument for allowing these devices to store recordings is largely that it allows the companies to review a small portion to correct errors, improve personalization, and generally improve the quality of responses offered by the devices.

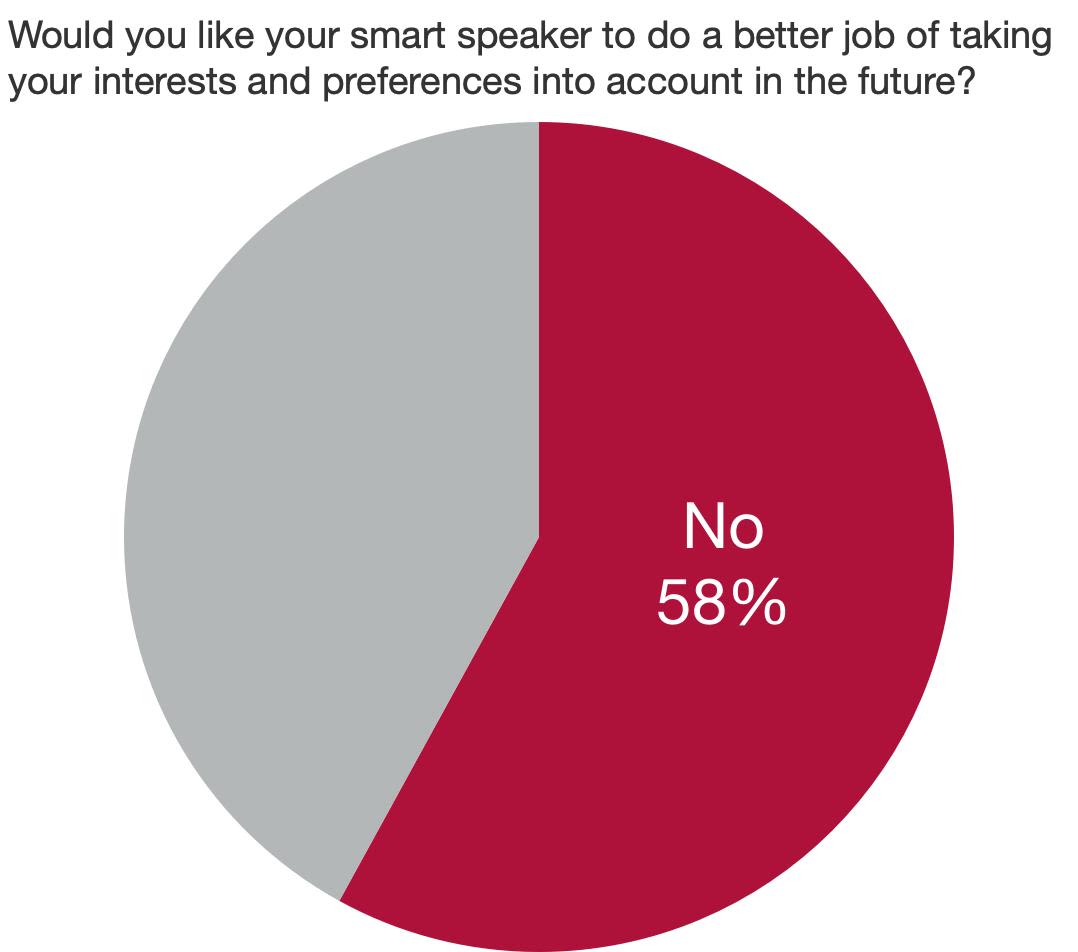

However, we see in the chart to the right that smart speaker owners often don't seem to want more personalization...

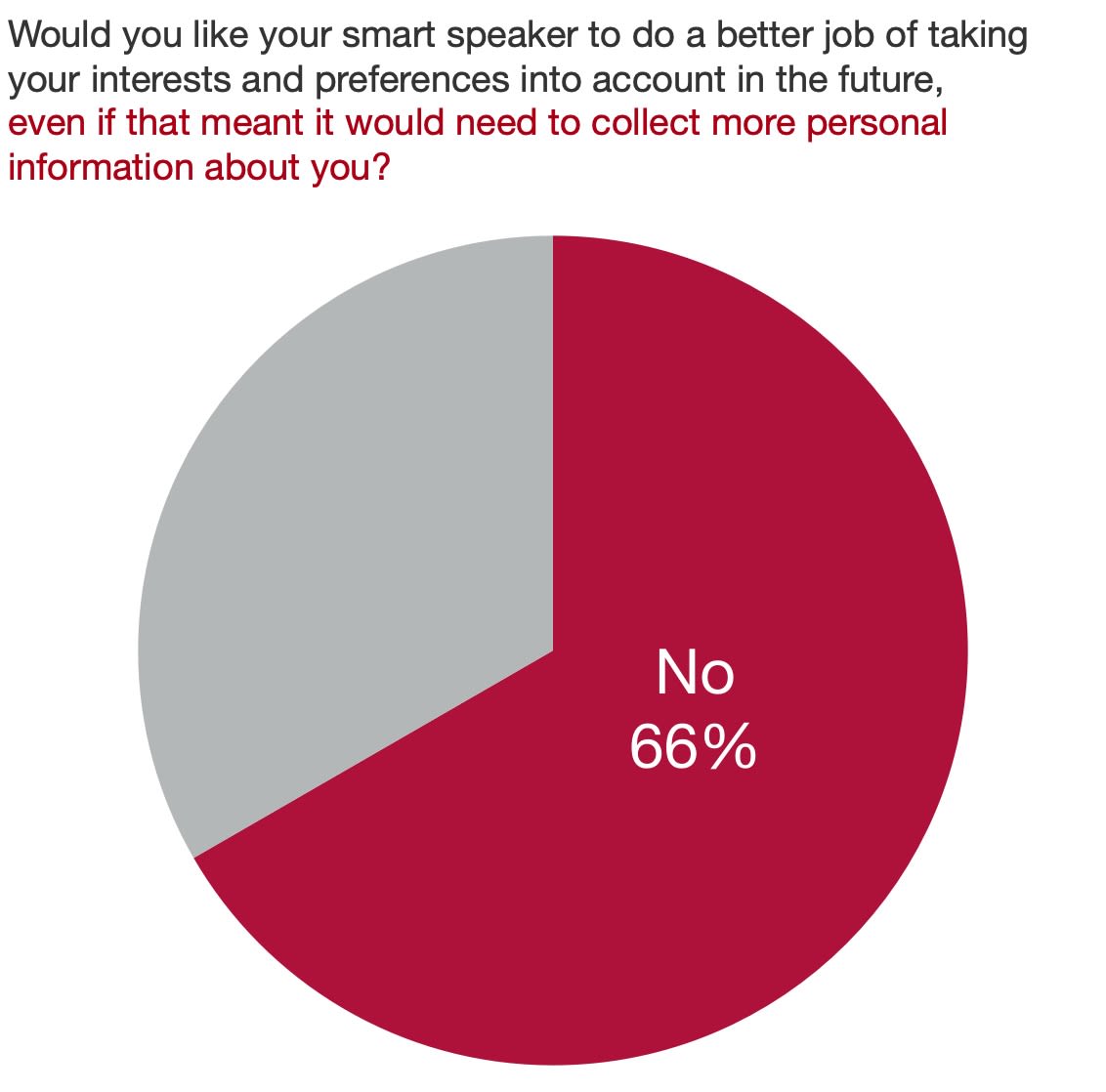

...and even fewer want it if it comes with the cost of additional data collection.

Privacy controls are cumbersome and rarely used

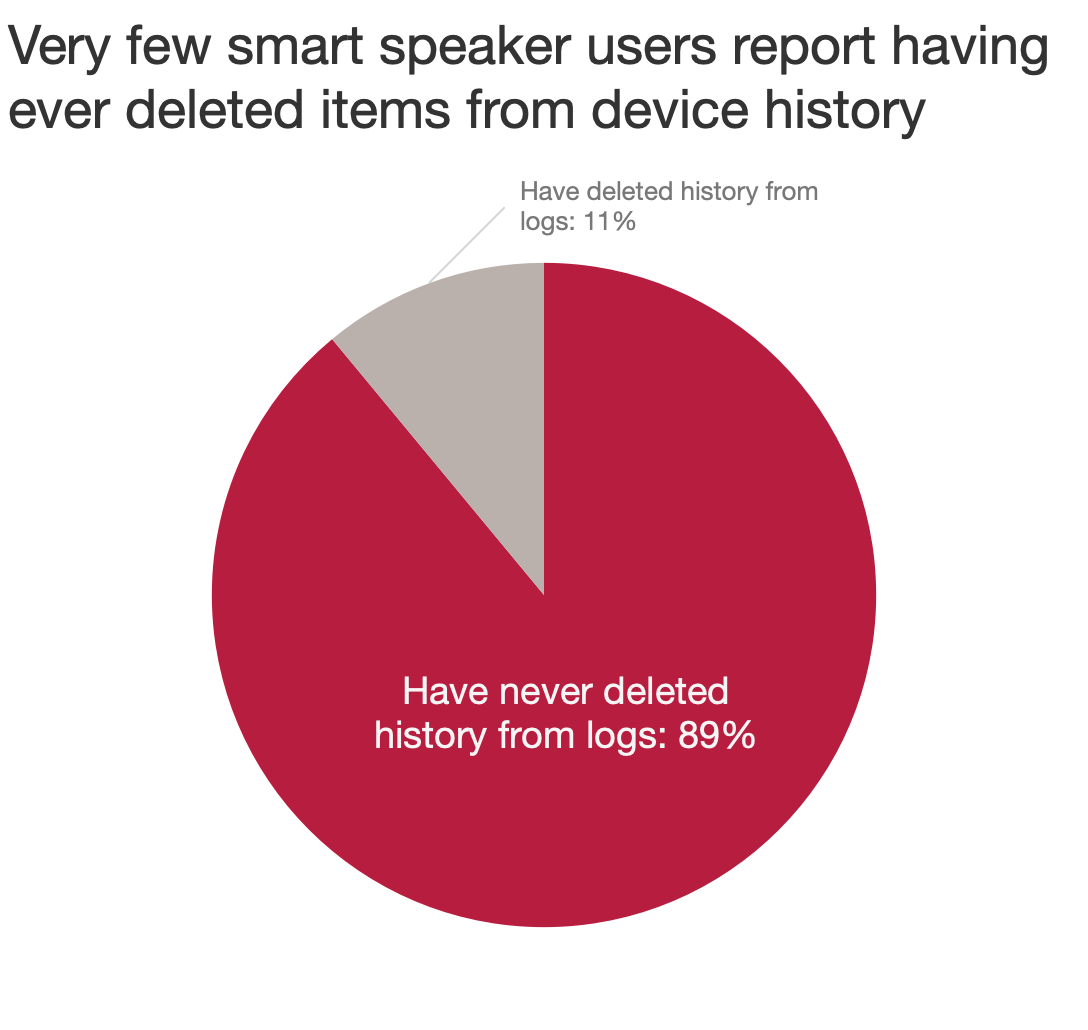

While some users report being concerned about data collection, the available data (Ammari et al., 2019) suggests that at least a quarter of users (26.8%) do not know that they can delete device history, and even fewer (11%) report having actually done so.

Another paper (Lau et al., 2019) also confirms that users rarely utilize the privacy controls available, including the mute button.

Based on these data points alone, we could certainly argue that users don't use these controls because they don't care about privacy and just don't have a desire to use them. However, we know that smart speaker owners in the Pew data cited above express concerns about data collection, and the Lau et al. paper indicates that the participants they interviewed thought privacy controls were cumbersome. Given those points, and the outcry after the April 2019 news discussed above, it seems that there is likely a meaningful subset of smart speaker owners (or potential owners) who might want to use privacy controls but don't find the controls currently available to be usable.

Data from: Music, Search, and IoT: How People (Really) Use Voice Assistants. T. Ammari, J. Kaye, J.Y. Tsai, and F. Bentley. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, Vol. 26, No. 3, Article 17. Publication date: April 2019.

Data from: Music, Search, and IoT: How People (Really) Use Voice Assistants. T. Ammari, J. Kaye, J.Y. Tsai, and F. Bentley. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, Vol. 26, No. 3, Article 17. Publication date: April 2019.

My data collection

Work cited above indicates that users find smart speaker privacy controls to be cumbersome. So how cumbersome are they? I collected some data points myself to find out a little bit more about the challenges a user would face if they wanted to turn off the setting pertaining to saving recordings (and thus leaving it available on the company's servers for employees or contractors to review).

Testing: Getting privacy information from voice interfaces

My results are limited to the devices I had access to: a Google Home Mini, an Amazon Echo Dot, and an iPhone. On the iPhone I also gathered data from the Google Home app that accompanies the Home Mini, the Amazon Alexa app for the Echo Dot, and the settings for Siri. (I couldn't test Siri on a HomePod because I didn't have the device, and Siri on an iPhone is a little different because it can utilize a screen along with the voice interface, but I did still gather data from Siri's settings.)

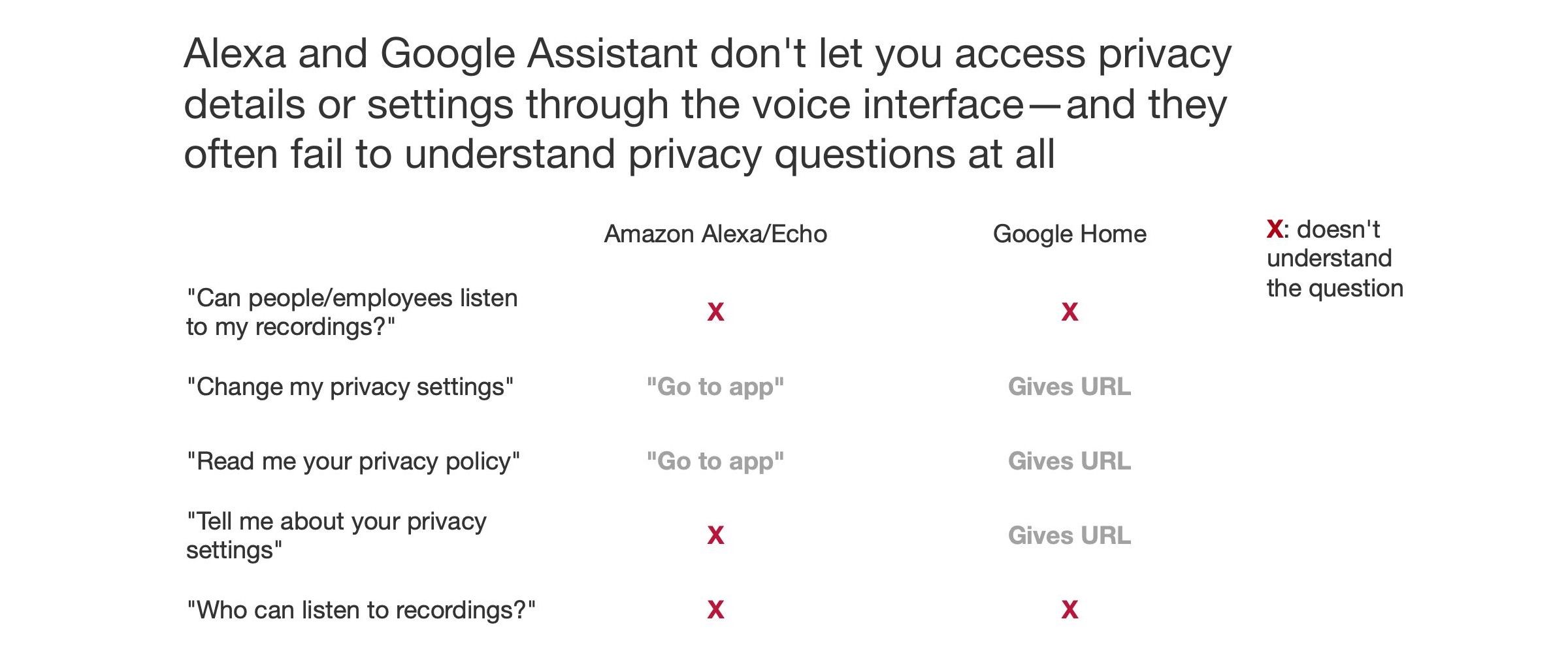

I asked the same set of privacy-related questions to an Amazon Echo Dot and a Google Home Mini. I recorded those interactions and categorized the responses.

I first took note of whether the device seemed to understand the question at all: I indicated that it did not if it explicitly said something like "Sorry, I didn't get that," or if it offered a nonsensical or irrelevant response like reading from a Wikipedia article or trying to play audio.

Then I took note of whether it could offer any meaningful information or make any changes to controls within the voice interface, and if it couldn't, what it told me to do to get information.

The results are summarized below.

Data collected from my own interactions with Amazon Echo Dot and Google Home Mini devices, February 2020. Apple not included here because I didn't have access to a HomePod, and Siri on a phone or other device with a screen isn't comparable in this context

Data collected from my own interactions with Amazon Echo Dot and Google Home Mini devices, February 2020. Apple not included here because I didn't have access to a HomePod, and Siri on a phone or other device with a screen isn't comparable in this context

Results: Getting privacy information from voice interfaces

Alexa could recognize questions about privacy settings or privacy policies, but it just directed me to the "settings in the Alexa app" for anything beyond a cursory response along the lines of "Amazon takes privacy seriously." It did not offer specific guidance about exactly what settings to look for. It did not understand questions about more specific privacy practices, such as whether Amazon allowed employees to listen to recordings.

Google Assistant was similar in terms of the set of questions it could or could not understand. It understood a question about privacy settings that Alexa did not understand, but this wasn't an exhaustive test, so that result might have been reversed if I had a different voice or phrased it slightly differently. Instead of directing me to the Google Home app, the Google device would often direct me to a URL. This alone would not be a very usable solution, but Google Assistant also automatically texts the URL to the associated smartphone when it does this, which was helpful.

This is of course not an exhaustive test, and to study this more closely, I would need to refine this approach, including testing different phrasings of questions and using different speaker voices. However, it's clear in any case that it's not easy to get privacy details from these two voice assistants, and I (a relatively expert user) couldn't find a way to change the privacy settings through the voice interface.*

*One exception: through Alexa, at least, I know you can tell Alexa to "delete the last thing I said." You can also, of course, use the mute buttons on the devices themselves, which doesn't involve the voice interface, but can be done without a separate device with a screen.

Some users may prefer to interact with settings in a visual interface anyway, but for convenience reasons—and also to maximize the accessibility benefits of voice assistants—it would make sense to offer the option of getting some privacy information through the voice interface wherever possible, and at least to make sure the device could understand and give intelligible responses to basic questions.

Testing readability of privacy information and controls

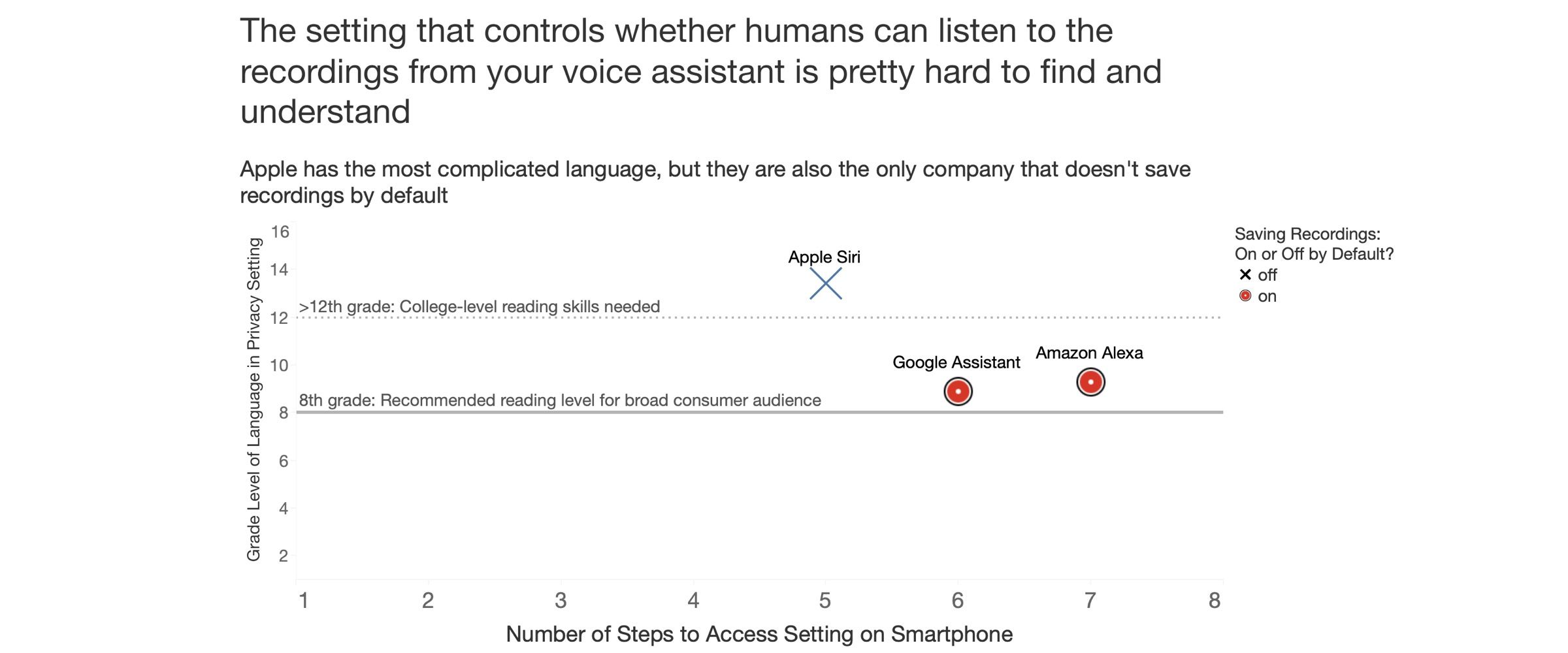

Next, I identified the setting relevant to turning off saving of recordings (and thus opting out of employees or contractors listening to those recordings) for each of the following voice assistants: Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, and Siri. My testing here is limited to the iOS apps that are used to control the corresponding smart speakers, so this may not be reflective of the Android apps or other platforms.

I collected two data points:

(1) The number of steps/taps/clicks that it took from the unlocked smartphone home screen to get to the setting

(2) The Flesch-Kincaid grade level score indicating the readability of the text explaining the setting

Results are summarized in the chart below.

Data collected from the setting relevant to turning off recording history / preventing recording history from being saved and used by the company in each of the following apps: Siri portion of Apple Settings in iOS, Google Assistant iOS app, and Amazon Alexa iOS apps. Readability scores for the language explaining those settings were calculated via https://www.webfx.com/tools/read-able/. Recommended reading level based on NN Group recommendations.

Data collected from the setting relevant to turning off recording history / preventing recording history from being saved and used by the company in each of the following apps: Siri portion of Apple Settings in iOS, Google Assistant iOS app, and Amazon Alexa iOS apps. Readability scores for the language explaining those settings were calculated via https://www.webfx.com/tools/read-able/. Recommended reading level based on NN Group recommendations.

Readability results

It took 5 steps to get to the Siri setting, 6 for Google Assistant, and 7 for Alexa. There is no hard line for what constitutes the "correct" number of clicks or "too many" clicks, but it did feel as though I had to dig through more layers of menus than necessary to find some of these settings. (This is of course anecdotal and subjective—more research is needed to see whether other users would agree with my assessment!)

Apple had the highest grade level (13.4 for the 22 words initially explaining the setting, and over 16—i.e., implying at least a 4-year college degree would be needed to —for the "more" explanation). Google Assistant and Alexa both explained their setting at about a 9th grade level, which was closer to standard recommendations, but it also took an extra step or two to find their settings.

Perhaps most importantly, however: Apple now has this setting turned off by default, so even though their language was the most complex, this arguably matters less since users don't need to find and understand the setting unless they want to opt in to their data being saved and used to improve Siri.

Conclusions

Overall, it seems that at least some meaningful portion of smart speaker users are concerned about the data their devices are collecting, but few users are currently using the privacy controls that the devices offer.

Based on my data collection, factors in the lack of use of privacy controls may include:

(1) that the voice interfaces themselves do not offer much in terms of privacy information or controls

(2) that the privacy information and controls available on the accompanying smartphone apps are not very easy to find or to interpret.

CALLS TO ACTION

- Do your research when buying and deciding how to use these devices. (You may even want to consider reading the privacy policies. I know, it's miserable—that's why we want to push companies to be better)

- Don't assume the device is making the right choices for you by default: find and consider changing your privacy settings!

- You may also want to use the mute button when needed to avoid accidental recordings of sensitive audio and learn how to delete specific interactions from the logs of your device.

- User studies are needed to understand how users prefer to receive privacy information (voice or screen) and whether they can understand current privacy interfaces.

- We will likely need to design and test voice-based privacy interfaces that let people get information and make informed choices.

- Once we have a better understanding of this space, we may need to argue for regulations (similar to the opt-out guidelines in CCPA for websites) to tell companies how to offer privacy information on voice assistants.