Preventing unnecessary environmental

and cultural decline

Lessons from the Newfoundland cod moratorium

This past summer, I went on a road trip to Newfoundland, Canada. Newfoundland is an island province on the far east coast of Atlantic Canada. I didn't know too much about the province besides that it was on the ocean and they had an Irish-sounding accent. After driving 9 hours from Port-aux-Basque on the west to St. John's on the east of the island and making stops along the way, I learned about the rich cultural history and traditions of Newfoundland culture. Newfoundland was founded and built on fish, more specifically Atlantic Cod. Cod is so entangled into their culture that when you get screeched in to be an honourary Newfoundlander you kiss a frozen cod during the ceremony.

This summer, I learned about the importance of fishing to the community, but also I learn about the terrible decline of their centuries-long fishing culture. Newfoundland's fishing industry fatally crashed over the past 50 years due to advances in technology, commercialization, and poor lack of enforcement leading to economic and cultural loss.

Standing on top of Gros Morne Mountain in Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland, Canada in August 2022. Photo by Mihai Mesko.

Standing on top of Gros Morne Mountain in Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland, Canada in August 2022. Photo by Mihai Mesko.

"Atlantic Cod Fish Swimming - Tynemouth Blue Reef Aquarium, Tynemouth, Tyne and Wear" by Glen Bowman

"Atlantic Cod Fish Swimming - Tynemouth Blue Reef Aquarium, Tynemouth, Tyne and Wear" by Glen Bowman

Fishing was the center of Newfoundland's culture and economy for hundreds of years. Only in the past one hundred years has the fishery started to decline for unnatural reasons. But, before discussing these reasons, it's important to know some more history of the island.

Newfoundland, a fishing community

Newfoundland is a province of Canada located in the North Atlantic Ocean. It was founded by an Italian explorer, Giovanni Cabotto, often anglicized to John Cabot, who discovered the island and that its' waters were filled with cod (History, 2022). Many Europeans settled in Newfoundland in hopes to create a better lifestyle and benefit from the economic opportunity of the cod fishery.

In my travels, I visited Bonavista, Newfoundland which was once the center of the cod fishing industry. Bonavista is disputed to be the original landing place of Giovanni Cabotto.

Newfoundland was not always a part of Canada. In the early 1900s, it was its own country. But, in 1949, Newfoundland decided to join Canada for economic security after its economy was hit hard by the Great Depression (Hiller, 1997).

Canada quickly realized the economic opportunity Newfoundland had within its cod industry. They invested in expanding and commercializing the industry. This can be seen in the dramatic increase in cod catches per year that started after Newfoundland joined Canada.

However, the thriving commercial cod fishery proved to be too effective.

The decline of the fishery

After joining Canada, the cod fishery exploded. Record amounts of fish were being caught up until the 1960s.

But, these record-setting numbers did not last long. In the 1970s, cod catches per year plummeted and thus the decline of the cod population began.

Many reasons contributed to the fall of the cod population (Mason, 2002):

- Overestimated cod stock size

- Quotas higher than stock estimates

- Local and foreign overfishing

- Low ocean temperatures

These governmental, scientific, environmental, and operational missteps all negatively impacted the health of the Nothern Atlantic cod stock.

Taking one example, poor fishing regulations and illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing led to a drastic depletion in the cod population. Looking at yearly fishing citations, much of the enforcement of catching IUU fishing did not occur until the cod moratorium when the government started enforcing fishing rules. Unfortunately, this enforcement was too late to help the cod population.

Factors contributing to the decline of the Atlantic Cod population (Mason, 2002)

Scientific

Overestimated cod stock: Scientists' estimates of the cod population were larger than reality and fishermen assumed that the cod stock was even larger in than the estimates. This resulted in overfishing.

Governmental

Quotas were higher than stock estimates: Government quotas on fishing were higher than the predicted stock estimates from scientists. This led to an unhealthy imbalance between cod births to cod catches.

Operational

Local and foreign overfishing: A disregard for stock estimates resulted in overfishing locally in Newfoundland, but also from foreign fishers. Illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing occurred on the edges of the Canadian ocean boundaries to contribute to the declining cod population.

Environmental

Low ocean temperature: Ocean waters over the past half century have been in decline. This has contributed to many cod migrating to warmer waters away from the coast of Newfoundland. This also contributed to the cod stock being overestimated.

Because the fisheries were so effective, the cod population could not reproduce fast enough to keep up at the rate they were being fished and consumed. Cod is now "vulnerable to extinction" (Oceana, 2022).

In a last-ditch effort to save the cod population, the Canadian government enforced a moratorium on the cod fishery in 1992.

Impact of the cod moratorium

The death of the cod fishery forced many Newfoundlanders to leave their homes and move away, often migrating to other provinces to find more profitable work.

In addition to migrating away from the province, since the 1950s, over 600 small fishing villages have been resettled to the urban centers of Newfoundland (Hidden Newfoundland, 2021). The province has worked to consolidate its sparse population, many of whom live in landlocked communities only accessible by boat, in hopes of providing a better quality of life. However, resettlement is taking away Newfoundlander's way of life that they've had for hundreds of years.

The total population of Newfoundland has declined as a result of the depleted cod population.

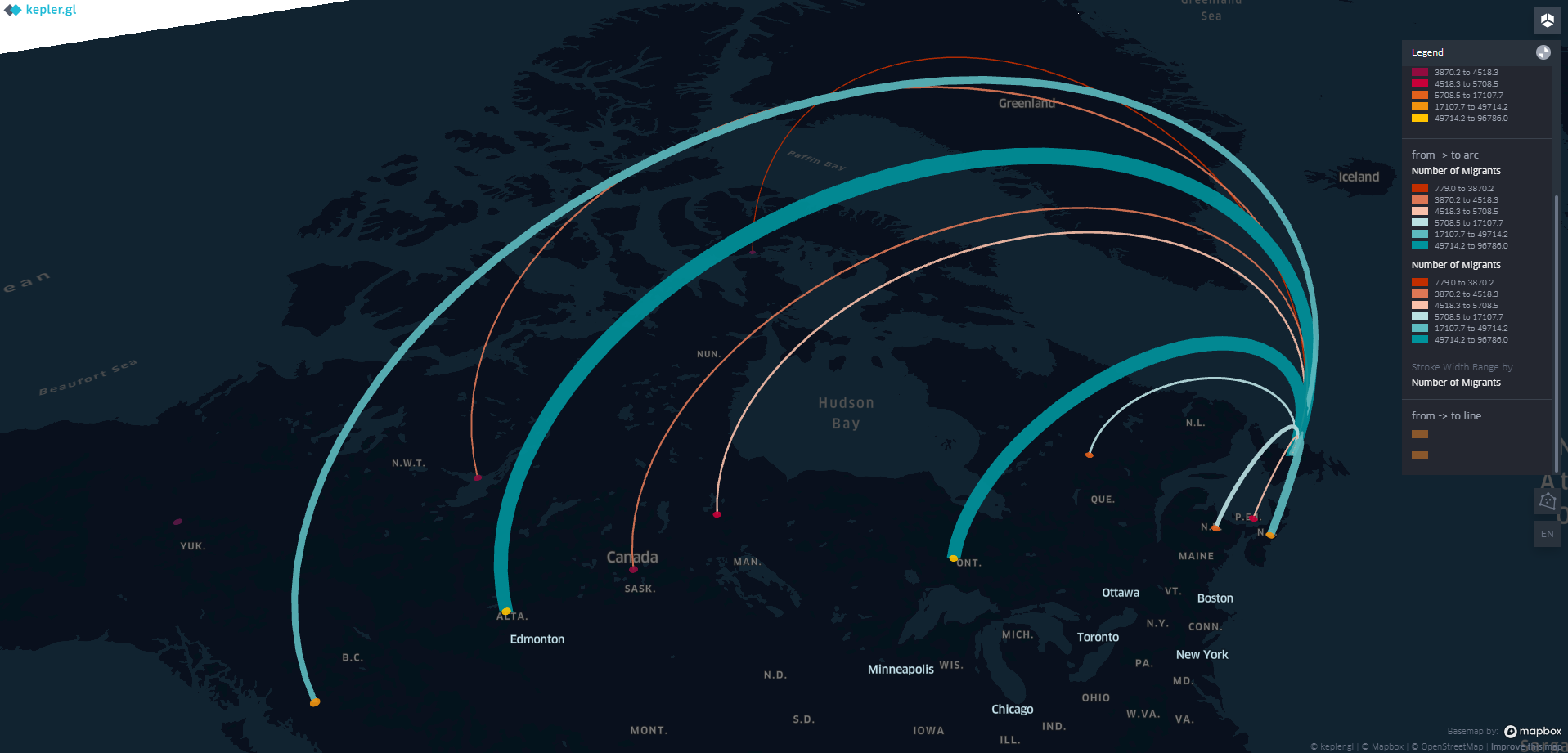

Since 1970, 300,000 Newfoundlanders have migrated to other provinces due to the decline in cod population and the moratorium. This interactive map visualizes where they when and the number of migrants to each province.

Newfoundland today

The cod industry and Newfoundlander's fishing culture are still recovering. The cod stock has seen minimal growth since the moratorium.

Newfoundlanders are optimistic and resilient people. During the screech-in, they speak about Newfoundland being the first to respond to the Titanic sinking and welcoming thousands of travelers that landed in Gander, Newfoundland during 9/11. Despite the moratorium, they will continue to pass on their fishing traditions and adapt to ensure their culture survives. Many cod fishermen have switched to the more lucrative shell fishing industry to continue their way of life on the ocean (Higgins, 2008).

To prevent the unregulated commercialization of industries and to protect the conservation of our oceans, there are a few steps you can take to protect Newfoundland and your own local community:

- Support local fishing by purchasing local seafood: You can find nearby fish markets using this search tool by LocalCatch. For Newfoundland, the government of Newfoundland produces a yearly Seafood Directory for consumers and businesses to source local fish.

- Vote for politicians and policies that support conservation: For Canada, you can find the conservation platforms for the federal political parties during the 2021 federal election here. For the US, you can see your local congress members history through the national environmental scorecard.

Sources

"Atlantic Cod Fish Swimming - Tynemouth Blue Reef Aquarium, Tynemouth, Tyne and Wear" by Glen Bowman is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/?ref=openverse.

Chair, A.W. (2006). Breaking New Ground: An Action Plan for Rebuilding The Grand Banks Fisheries. Sustainable Management of Straddling Fish Stocks in the Northwest Atlantic. https://www.gov.nl.ca/ffa/files/publications-archives-pdf-breakingnewgroundadvisory2005.pdf

Hidden Newfoundland. (2021). The Resettlement Program and Abandonded Communities. https://www.hiddennewfoundland.ca/resettled-communities

Hiller, J. K. (1997). Canada and the Newfoundland Crisis, 1929-1934. Heritage. https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/politics/economic-crisis-1929-1934.php

Higgins, J. (2008). Economic Impacts of the Cod Moratorium. Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador. https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/economy/moratorium-impacts.php

History. (2022). John Cabot. https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/john-cabot

Mason, F. (2002). The Newfoundland Cod Stock Collapse: A Review and Analysis of Social Factors. Electronic Green Journal, 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.5070/G311710480 Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/19p7z78s

Oceana. (2022). Atlantic Cod. https://oceana.org/marine-life/atlantic-cod/#:~:text=Scientists%20agree%20that%20North%20Atlantic,currently%20considered%20vulnerable%20to%20extinction.

Rebecca Schijns, Rainer Froese, Jeffrey A Hutchings, Daniel Pauly, Five centuries of cod catches in Eastern Canada, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 78, Issue 8, November 2021, Pages 2675–2683, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab153

Roy, N. et al. (2006). _The fishery as economic base in the Newfoundland economy._IIFET 2006 Portsmouth Proceedings.

Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0005-01 Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex, https://doi.org/10.25318/1710000501-eng

Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0022-01 Estimates of interprovincial migrants by province or territory of origin and destination, annual, https://doi.org/10.25318/1710002201-eng

Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0229-01 Long-run provincial and territorial data DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/3610022901-eng

This article was made as a class project for Telling Stories with Data at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in October 2022.

Made with ❤️from an honourary Newfoundlander. Photo in Trinity, Newfoundland by Kelly McManus.

Made with ❤️from an honourary Newfoundlander. Photo in Trinity, Newfoundland by Kelly McManus.